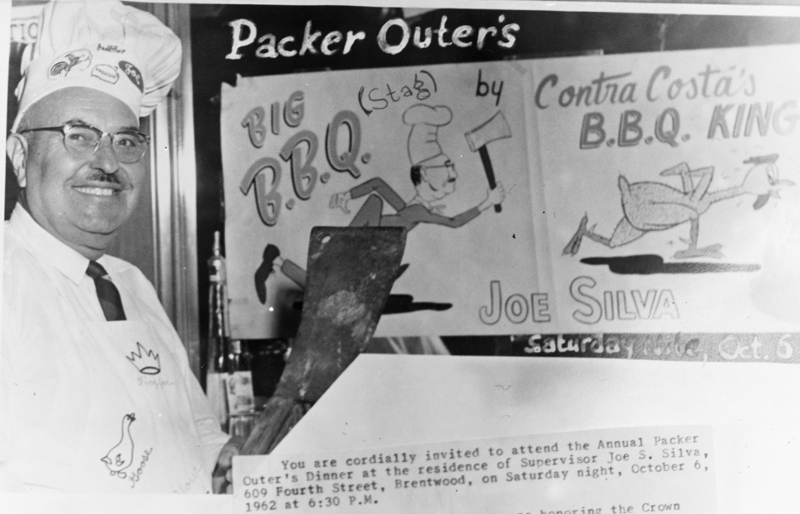

Joe Silva — The Man who saved BART

CONTRA COSTA COUNTY, CA (July 21, 2022) — At 5 a.m., Joe Silva sat on a stool in Lasell’s, a counter-service-only breakfast stop in Martinez, in July 1962. The screws were being tightened on this Contra Costa County Supervisor.

In the door stepped San Francisco Mayor George Christopher, Oakland Mayor John Houlihan and BART Board President Adrien Falk. Silva held the swing vote among the five county supervisors on the board, and they needed his yes vote. That afternoon the supervisors would vote on whether to put a general obligation bond for a new regional rail system on the November ballot.

Silva had refused to meet in San Francisco. Because of this, the three politicians had driven to meet him — a farmer used to this ungodly hour — on his home turf. They came to twist Silva’s arm.

Original plans for a new Bay Area Rapid Transit District included Marin County and San Mateo County. However, both counties had dropped out. The bridge authority refused to allow trains on a second deck of the Golden Gate bridge. Marin County considered a tube to Sausalito too expensive. San Mateo County didn’t want taxpayers getting on the hook for BART since commuters could already use Southern Pacific Railroad.

Going to the voters

The proposed BART system dropped down from five counties to just three. San Francisco and Alameda Counties had decided to put BART to the voters, but a two-county system didn’t pencil out. Agreement by Contra Costa County for a bond election was essential to make BART financially feasible.

Silva had been under tremendous pressure. Two of the five supervisors had already announced their opposition and two were in favor. The Contra Costa Times newspaper recommended a yes vote for a rapid transit system. Governor Pat Brown had personally called Silva to ask him to let the voters decide on the bond measure.

Brentwood farmers in Silva’s hometown and other constituents in Silva’s district, which was in the far eastern agricultural area of the county, were opposed. “What’s in it for us?” they asked, believing the train would only benefit commuters who worked in Oakland and San Francisco. Without Silva’s vote, there would be no BART.

The three out-of-town politicians tried for at least an hour to get a commitment from Silva. Houlihan wondered what he wanted for his vote, but Silva was tight-lipped about what he was going to do. They left worried that they had failed.

Later that day, the Contra Costa County Supervisors gathered to vote on whether or not to put the BART general obligation bond measure on the ballot. “Shall the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District incur a bonded indebtedness in the principal amount of $792,000,00 for the object and purpose of acquiring, constructing and operating a rapid transit system…?” The two against voted no, the two in favor voted yes, and then it was up to Silva. After a long pause, he voted yes.

Many obstacles

Voters did pass the measure by a slim margin in November 1962. Many more obstacles were ahead until the first train started service ten years later on September 11, 1972. But none of this would have been possible without the fortitude of Joe Silva, despite threats and personal stress, to do what he thought was best. If he voted as he did, Mayor Christopher had told him, “You’ll be known as the man who made it possible.” And he is.

I’ve always liked this anecdote because of its lessons about leadership. Unlike in Congress or the State Legislature, when someone serves on a local board, such as a five-member board of supervisors, the elected official can’t hide behind an abstention. If Silva had abstained, the motion would have failed because his abstention would count as a no vote.

He forced the elected petitioners to come to him on his own time and in his own county. He did not want to risk the perception by his constituents that he was wined and dined in the fancier citified districts for his vote. Possibly surprising Oakland’s mayor, he didn’t want something to trade for his vote. He weighed the pros and cons—what would be good for the whole county in the future versus the cost to voters in his agricultural district. He knew he would face the ire of those constituents. Joe Silva was elected to make decisions, and he did. One vote changed history, and we have him to thank for it.

Notes about this story

I’m indebted to Mike Healy, who wrote the book “BART: The Dramatic History of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System.” Although I’ve known this story for years, I was able to summarize it authoritatively for you by consulting his book, particularly pages 53-57. Mike Healy worked as the head of BART’s Media and Public Affairs for 22 years. I recommend his entertaining and informative book.

Gail Murray, a former BART director, served as Walnut Creek mayor and council member. She also served as the chair and member of the Board of Directors for the CCCTA. The author wrote “Lessons from the Hot Seat: Governing at the Local and Regional Level.”