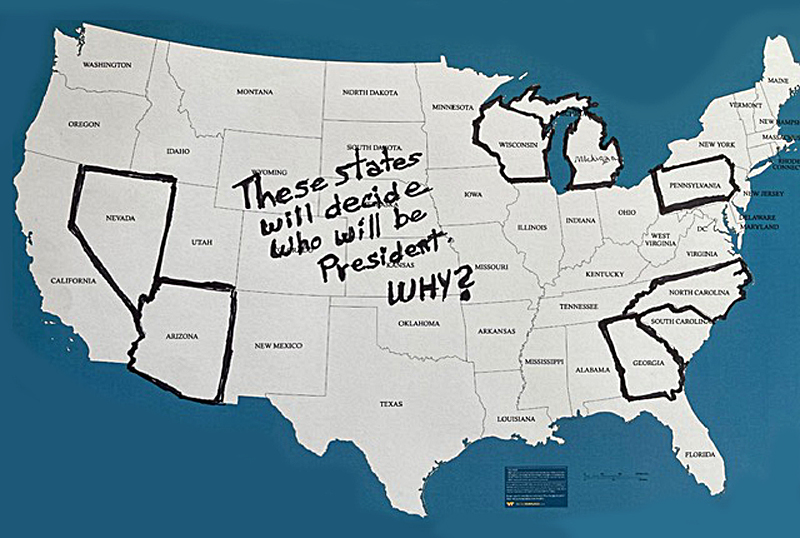

Why do seven states decide who’s president?

(Oct. 29, 2024) — Why do seven states get to decide who’s our president?

It’s because of our unique system to elect a president and vice-president called the Electoral College. The system was created as a compromise in the racism of 1787 and embedded in our Constitution.

When you vote for Harris or Trump in this 2024 election, you are actually voting for a slate of Electors. This year it’s not clear who will win the slate of Electors in seven of the states. These battleground states will decide the election.

How the Electoral College works

Article 2 Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution states that each state shall appoint Electors to vote for President and Vice-President. We name that body the Electoral College.

The number of Electors totals 538, based on the size of each state’s congressional delegation—how many members it sends to the House of Representatives plus its two Senators. In order to win, a candidate for president needs over 50%, or 270 electoral votes. According to the Constitution, if no single candidate wins a majority of the electoral votes, the decision goes to the House, where each state gets one vote.

All but two states, Maine and Nebraska, are “winner-take-all” states. That means that whichever candidate gets the most votes wins the state, regardless of how many votes the other candidate gets. For example, in my state of California, which is overwhelmingly Democratic, Harris will get all the electoral votes and Trump will get none, no matter how many citizens voted for him.

Many people think that when they vote for Harris or Trump they are voting for the president. Not so. They are voting for a slate of Electors nominated by their political parties. In most states, Electors are pledged to vote for the top candidate who won their state (although sometimes they go rogue).

Who can name the Electors voting on their behalf in their state? Not me.

Here’s where the seven states come in to decide our election. Voters in Pennsylvania, Georgia, North Carolina, Michigan, Arizona, Wisconsin, and Nevada can swing either way—they are not majority Democrat or Republican. They’re the battleground for electoral votes because who will be the winner is not clear. Will all their electoral votes go to Harris? Or will all their electoral votes go to Trump? We probably won’t know until election day.

The battleground states have changed from election to election as the population and the political leanings have changed. For example, Virginia and Colorado previously qualified as competitive states. In the 2000 race between Gore and Bush, Florida was a swing state but is no more. In 2016, there were 16 swing states, but now there are only seven.

In five previous elections, the President won the electoral votes but didn’t win the popular vote. The most recent was when Trump won 304 electoral votes over Clinton’s 227, although Clinton had 2,868,686 more popular votes.

Why is the Electoral College in our constitution?

I always thought the Electoral College was sacred because it’s in the Constitution. But it turns out that the origin of the Electoral College is not at all sacred: it’s a result of our racist past.

During the Constitutional Convention in 1787, the Founding Fathers argued about how to pick a president. They didn’t have good models for our country’s chief executive: tyrannical kings, colonial governors, other despots. The idea of a popular vote was rebutted by some as too difficult for voters to become informed in a rural country.

(Of course, only white male landowners could actually vote.) Out of that debate, the idea of Electors was born.

But even after their compromise to appoint Electors, slavery was still the most divisive issue. Slavery was critical to the economy of North and South Carolina, Virginia, Georgia, and Maryland. Five northern states had passed legislation to end slavery, but these five largest slave-holding states would not agree to the Constitution if it called for the abolishment of slavery. Roughly 40% of their population were enslaved. After 32 votes in 21 days of debate, the Founders were at an impasse.

Eleven of the delegates were appointed to resolve the issue. The compromise was to count slaves as three-fifths of a person in the census, greatly increasing the census numbers of the southern states. But counting 60% of the enslaved in the census gave southern states additional appointees to the Electoral College, resulting in more political power in Congress. As a consequence, Virginia, with more than 200,000 slaves, got a quarter of the votes for president. A Virginian, George Washington, was unanimously elected our first president.

I had understood that the main discord among the Founders was over the power of large states vs. small states. Although it was resolved with the creation of Electors, the issue that cemented the votes for our Constitution with an Electoral College was slavery.

Should we change to a popular vote for president? Can we?

There are active efforts to change our federal elections from the Electoral College to the popular vote.

The League of Women Voters, representing 700 state and local Leagues, is leading a grass roots effort to amend the Constitution. It notes that because the Constitution has been amended 27 times, it’s not impossible. Amendments have occurred during periods of great crisis and conflict, and the League believes this is one such time, when so many people are disaffected. Because of this discontent, voter participation has declined. The popular vote will demonstrate that one’s vote actually does matter. In my California example, Republican votes will count toward the total popular vote instead of being absorbed in a winner-take-all state total.

Article V of the Constitution outlines the requirements to amend the Constitution.

- The process begins with a bill introduced in Congress for an amendment. It then requires

- two-thirds majority vote of the House of Representatives

- two-thirds majority vote of the Senate

- sent to the Governor of each state for a vote of its legislature or a state convention

- three-fourths of the states ratify (38 of the 50 states)

- published in the Federal Register as a completed amendment.

In 2019 a bill was introduced in both the House and Senate, but no vote has yet been taken. In former years, a bill passed 338-70 in the House but died in a Senate filibuster, demonstrating that there can be consensus, albeit many obstacles to success. Unlike political or academic attempts in the past, the League calls its effort a promising “moonshot” based on its grass roots leadership to organize, educate, and advocate for this change.

One objection that has been raised is that the popular vote advantages large states over small. On the contrary, the 50 largest cities represent only 15% of the country’s population, while rural states represent 14%, almost as many people. Small towns and suburbs represent the most at 71% of the population. The analysis of previous elections also concludes that is a non-partisan issue, not benefiting Democrats over Republicans.

The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact is an agreement among a group of U.S. states and the District of Columbia to award all their electoral votes to whichever presidential candidate wins the overall popular vote in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Eighteen of the states and the District of Columbia needed to make the popular vote the law are on board, accounting for 209 of the 270 needed to win.

According to the National Popular Vote website, Article II of the Constitution “gives the states exclusive control over the choice of method of awarding their electoral votes—thereby giving the states a built-in way to reform the system.”

Article II, Section 1 states: “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in Congress…”

The Compact’s method is much simpler than the process outlined by the League of Women Voters for a Constitutional amendment. The presidential election would cement the belief of one person/one vote just like all our other elections are decided. It doesn’t need Congressional ratification and it doesn’t need a Constitutional Convention. It uses the power that exists in the Constitution: The states have the right to assign all their electoral votes to the person who wins the most votes in the national election. Relying on Article II assures that when the states achieve the 270 electoral votes, the popular vote becomes law.

Conclusion

The Electoral College was born from a compromise to equalize the voting power of the more populous northern states and the slave-holding states in the south. These two efforts to change to a popular vote, while retaining the words set down in the Constitution, acknowledge that the current archaic system has outlived its purpose.

Today one person’s vote carries more weight depending on where they live. Based on a popular vote, the current 43 states that are basically ignored in campaigns, except for fundraising, will be back in play. Seven states will not be the decision-makers—all of us will have a voice. Changing to the popular vote will show that the President and Vice President are chosen and beholden to all Americans, not just separate states.

Resources Consulted

- https://www.archives.gov/electoral-college/history

- https://www.nytimes.com/article/the-electoral-college.html

- https://www.history.com/news/electors-chosen-electoral-college

- https://rollcall.com/2022/12/13/how-the-battleground-states-have-shifted-over-the-past-decade/

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/elections/interactive/2024/2024-swing-states-trump-harris/

- https://www.americanacorner.com/blog/constitutional-convention-slavery

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kxNNys7CX88 (League of Women Voters)

- https://www.nationalpopularvote.com/written-explanation

- https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/constitution

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OpGKvHlqU5 (National Popular Vote Interstate Compact)

Gail Murray

Gail Murray served in Walnut Creek as Mayor and city councilmember for 10 years. From 2004-2016 she served as District 1 Director, Board of Directors of the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District (BART). She is the author of "Lessons from the Hot Seat: Governing at the Local and Regional Level."