May the force(s) be with us

Since recorded history and likely before that, humans have been observing the universe and trying to make sense of it.

Since recorded history and likely before that, humans have been observing the universe and trying to make sense of it.

What are things made of and what governs how they interact? These are big questions, so I’ll break it down and focus today on forces.

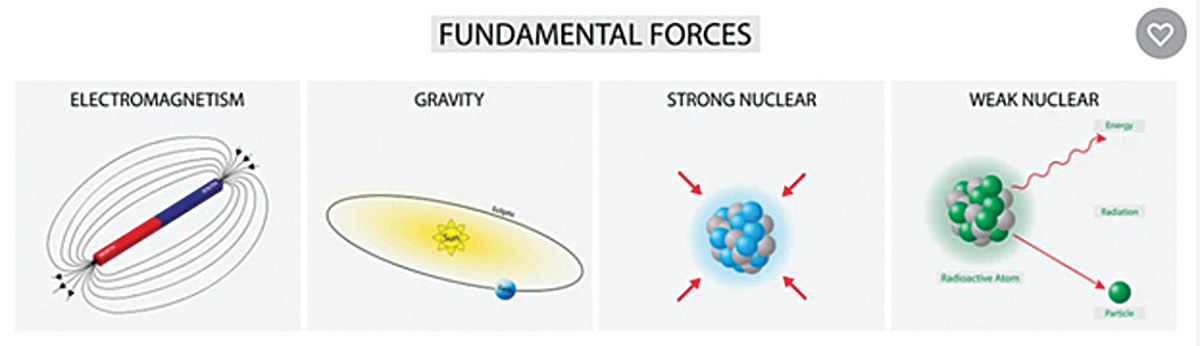

We now know that there are at least four fundamental forces. There may be a fifth force, but that idea is “under development.”

The one that everyone is most familiar with is gravity. This is the force of attraction between any two objects: the sun and the earth, you and the earth and even a couple of paper clips.

Though there were centuries of alternative ideas, Isaac Newton published a comprehensive theory of gravity about 300 years ago.

In 1665, he moved from London where he was attending Trinity College to his boyhood home 60 miles away to avoid the plague that was ravaging the city. (Sound familiar?) This was the site of the famous falling apple that got him started. It didn’t actually hit him on the head, he just saw it fall.

He also invented calculus and the laws of motion and produced important work on optics and the theory of colors.

General Theory of Relativity

Then just 100 years ago, Albert Einstein published his General Theory of Relativity that described gravity in a more detailed and fundamental way.

Another one that we are pretty familiar with is the force between charged particles. The magnetic force acts between moving charged particles and the electric force between stationary charged particles.

They arise from the same fundamental force, called the electromagnetic force. This is the force responsible for holding atoms and molecules together, making motors turn and other everyday phenomena.

Electric charges are either positive or negative. Like charges repel each other and unlike charges attract each other with exactly equal strength. This means that matter sticks together in neutral clumps – like us.

Though gravity and the electromagnetic force each have an infinite range that reduces with the square of the distance, the electromagnetic force is much, much stronger.

Here’s an example. If you are standing 3 feet from someone, you won’t feel the gravitational attraction. However, if each of you had an excess electric charge of just 1 percent, the force between you would be about equal to the “weight” of the earth.

Strong and weak forces

The last two forces deal with the nuclei of atoms. The force that holds a nucleus together is called the “strong” nuclear force, well, because it is the strongest force we know about and because physicists are not very good at making up names.

Besides doing the job of holding nuclei together and providing us with the elements of which everything is made, it is also responsible for the nuclear interactions that power the sun. The reason that we don’t observe this force directly is that it operates at a range about the size of a nucleus.

The fourth and final force is called the “weak” nuclear force since it is weaker than the “strong” force. It is still much stronger than gravity but about 10 trillion times weaker than the electromagnetic force.

It is the only force that allows some particles to change into other particles. Weird, huh? An example you might be familiar with is radioactivity, where a neutron becomes a proton and vice versa. These processes lead to the rich variety of elements we observe.

There you have it. Four fundamental forces; gravitational, electromagnetic, strong and weak. All very different and all important.

Steve Gourlay

Steve Gourlay is a career scientist with a PhD in experimental particle physics. He recently retired after working at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, CERN (the European Center for Nuclear Research) and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Send questions and comments to him at sgpntz@outlook.com.